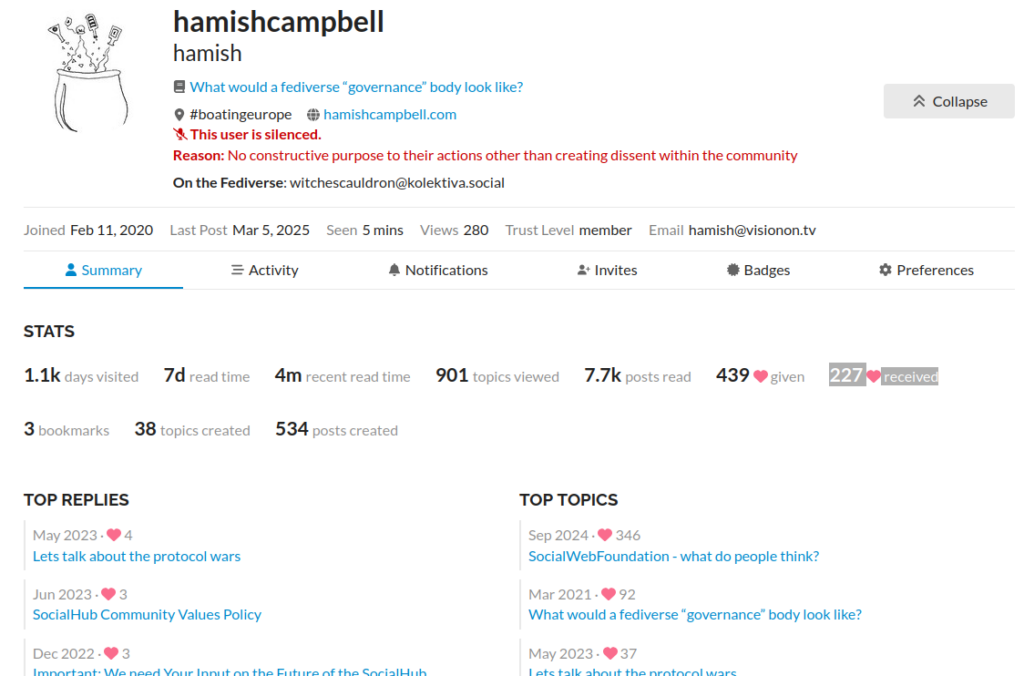

A talk on a new book by Pepper Culpepper on how corporate scandals could be used to save liberal “democracy”. This talk is the familiar fantasy of elitist institutions like the Blavatnik School, Oxford. Culpepper and co author Lee reframe disasters from Enron to Cambridge Analytica not as structural failures of a system built to concentrate power, but as healthy “corrections” that supposedly can be used by people like them to renew democracy.

In this telling, public anger is something to be safely channelled into regulation, corporations remain indispensable, and democracy survives as a managerial process overseen by the normal “progressive” liberalish policy priests. It is #deathcult logic, polished up, to worship the system while denying its violence, recurring catastrophe not as proof of collapse, but as evidence that the machine still works – if only the right people are allowed to control it.

The Blavatnik worldview in one sentence “Capitalism is broken, but only experts can fix it, without threatening those who benefit from it.” The tone is elitists pessimism dressed as realism, the talk opens with managed the pessimism “Yes, things are bad…” “…but lives are improving” “…and the liberal order still basically works” “…we just need better policy”. Everything else is ornamentation, democracy is talked about constantly, but control is never offered.

This is the #deathcult chant, not in any way apocalyptic enough to demand rupture, and also not hopeful enough to empower people. It’s pessimism, justifying elitist management, so no real change. They talk about democracy, but notice how it’s framed: Democracy = policy capacity, regulatory competence, party systems and institutional continuity. Democracy is not found in any real popular control, public ownership, exit, refusal, redistribution, or material power. The people appear as voters, outrage generators, legitimacy providers, but never as agents who might take any part in control, the old mainstreaming tradition of social democracy as crowd management.

The book is worship of policy nerds vs fear of the #techbrows, a strange inversion at work, that billionaires are dangerous, reckless and markets are running amok. The solution for them, is therefore, “we need policy experts to save us.” who can circulate through the same elitist institutions, depend on the same funding systems and never threaten ownership or accumulation. Yes, capitalism is “broken” – but only as a governance problem to solve. This is instead of any stress of public vs concentrated power, in their book, it’s an intra-elite turf war, sold as democracy.

They get very close to truth here “capitalism is a minority of people with a lot of power, unafraid to use it.” But then they refuse any logical conclusion, if what they say is true, then regulation is insufficient, as any real accountability requires ownership change and democracy requires material leverage to function. Instead, they do a quick pivot to stakeholder capitalism and value generation as a path to “put capitalism back on its feet”. This is a system that’s killing people, while insisting itself must stay alive.

Public capitalism is a bloodless fantasy that might sound radical to a privileged chattering class. But it’s the same failed mess, were the public gets, exposure, risk, volatility while the elitists keep control and set the agenda. It is inequality, endlessly acknowledged, but never touched, the normal elitists preference disguised as inevitability.

There, assumptions are wrong, yes, the is a very real fear of autocracy, but not of oligarchy, they are worried about autocracy, but they are not worried enough about billionaires controlling media, capital, thus veto over policy, regulatory capture and economic coercion. Why? Because oligarchy is their ecosystem. Autocracy is framed as something external, crude, foreign, where oligarchy is polite, networked, respectable… and pays for book launches at the Blavatnik School we sip wine at after the event.

They are scared by “bad populism” but love “good populism” as outrage without power, believing, outrage can be used to drive a very narrow idea of reform, scandals and anger can be “harnessed” as a fuel for what they see as elitist balance. The public is a matchstick, a controlled burn to open up a space for their class (literally their children) the future“policy entrepreneurs” who, with generational wealth, still rich enough to volunteer, bored enough to care and insulated enough to fail, its politics as a hobby of the ideal rich.

In the Q&A they talk about media fragmentation = democracy in trouble (but not elitist paths). They worry we “can’t agree on facts”. But they don’t worry about who owns platforms, who shapes narratives, who funds think tanks, who sets the Overton window. Fragmentation is blamed on the public, concentration is never blamed on capital. Then we have #AI outrage already being pre-neutralised, the AI bubble “will pop”, they say. The question is, “how do we use that outrage?” Not, how do we let people decide, how do we transfer control, how do we prevent enclosure in the first place.

Outrage is something to be channelled into managerial politics with the Churchillian cop-out “democracy is the worst system except all the others.” Which translates into, lower expectations, accept elitist rule to manage decline politely.

In this path, corporations are treated as unavoidable, people are treated as incapable, you get a strong feeling from this talk and book that this is it is not democratic theory, rather paternalism with footnotes. The core lie, unspoken underneath everything, is “we can fix capitalism without shifting power.” Every answer assumes that capitalism must remain, corporations must remain, and that the elitists must mediate and guided the public not to challenge this.

It’s elite self-soothing, but yes, they aren’t wrong that the system is broken, they’re wrong about who is allowed to fix it.