Ten years ago – and honestly long before that – there were endless conversations on #failbook about how useful it was for campaigning. The dominant view back then was simple: it’s just cat memes, it’s just tooling, it isn’t political so we can use it harmlessly. Before Snowden, this wasn’t a fringe view – it was probably a 90% consensus, especially among activists, and #fashionista tech communities. I’m not pointing fingers here, as this was normal. Many of us – including friends and collaborators – believed this.

And that’s exactly why we need to remember it. If we forget, we repeat, if we scapegoat, we learn nothing and become no better than the trolls. The problem isn’t individuals – it’s collective amnesia. The is an issue of responsibility and historical memory, that when people deny their own history of responsibility, they disconnect from reality. That’s how too meany people drift into the same “post-truth” space we criticise in figures like Trump or Stammer, where inconvenient past positions are quietly erased.

The uncomfortable truth is that many of us argued that #dotcons were neutral platforms, engagement was empowerment, memes were harmless cultural glue. Meanwhile, our healthier #openweb tools were neglected and dismantled, community infrastructure withered, while the #closedweb platform economy consolidated power. Looking back isn’t about blame. It’s about understanding how we arrived at this mess.

The campaigning trap? Ironically, many tech-minded activists used to run workshops teaching people how to campaign on #dotcons – even as we recognise that these platforms structurally undermine autonomy, community governance, and sustainable organising. This didn’t only happen because people were stupid or malicious. It happened because convenience replaced infrastructure building, the #geekproblem undervalued usability and social design and short-term reach trumped long-term resilience. The result is a paradox: we built our movements inside systems that weakened them.

But spreading more shit without composting it – just makes alternative spaces smell worse and drives people away. This mess is not history, it’s now. This conversation isn’t nostalgia or score-settling. It’s about the present and future. Looking back is how we understand structural mistakes to rebuild shared memory and #KISS avoid repeating cycles of platform capture.

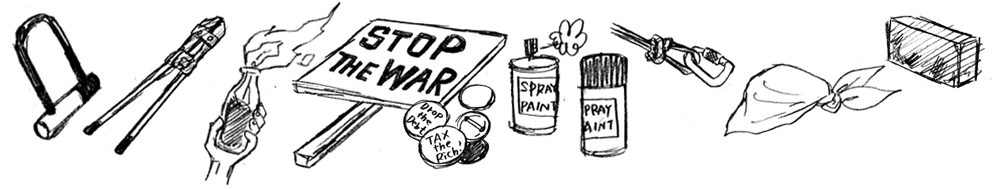

The compost metaphor is useful, #OMN is a spade not a weapon – a tool. A spade digs, turns soil to compost what came before. The mess we helped create – the attention traps, the algorithmic silos, the dependency on corporate platforms – isn’t something to deny or hide, it’s material to compost into something better.

The choices we made then still shape the terrain we stand on today. It’s the #fashernista problem, one of the biggest blocks to building real alternatives is this #fashernista dynamic – activism as aesthetic performance rather than infrastructure building. It looks radical, It feels good, but it rarely produces durable tools or collective power. Real alternatives require slower, less glamorous work of maintaining systems, building trust networks to support messy grassroots processes and designing for longevity rather than attention spikes.

A bridge forward? As I keep saying, this isn’t about shame or purity politics. Almost everyone followed the same path because the incentives pointed that way. The real question is that now that we know better, what do we build next?

#OMN isn’t nostalgia for a lost web – it’s an attempt to learn from past failures and construct a media infrastructure that remembers history to support collective agency and avoids repeating the mistakes that led to the current #dotcons landscape.

This message is a shovel. The question is whether we use it to dig trenches against each other – or to prepare soil where something better can grow.