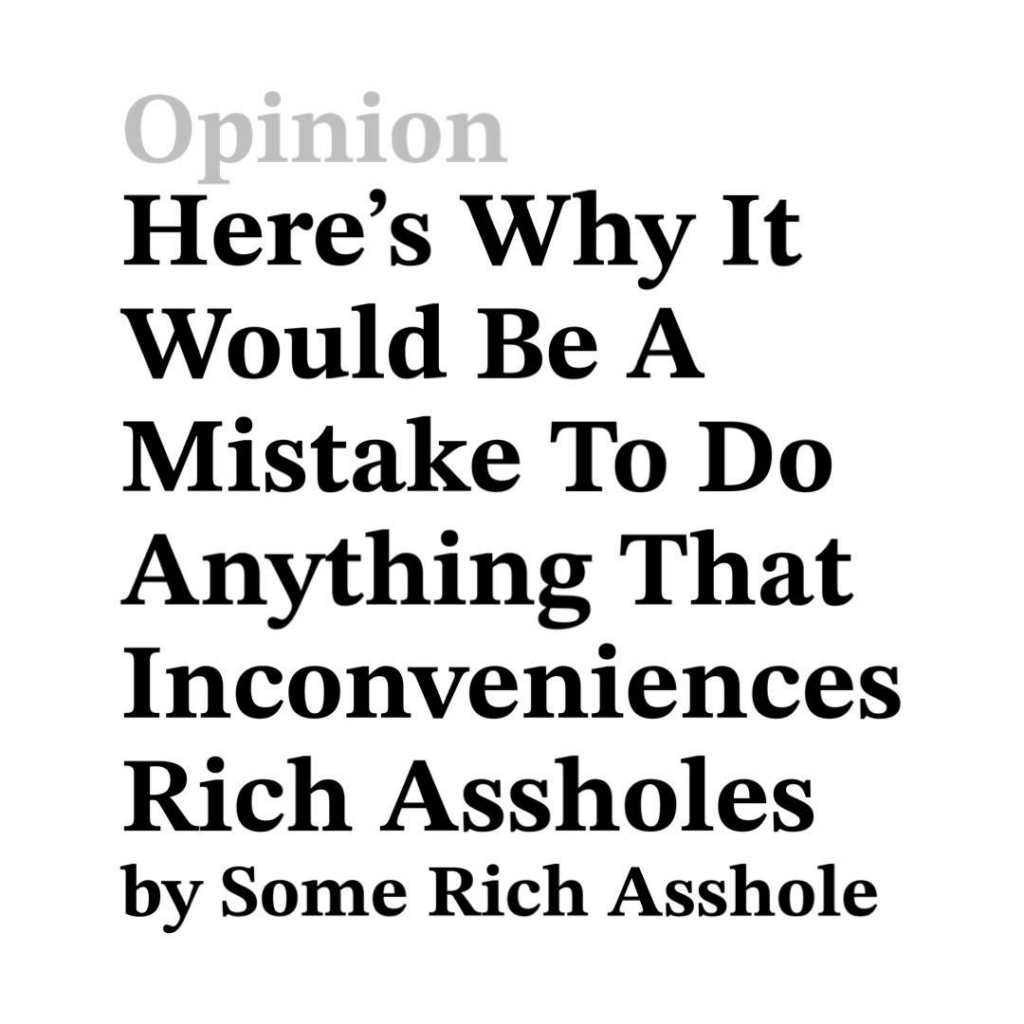

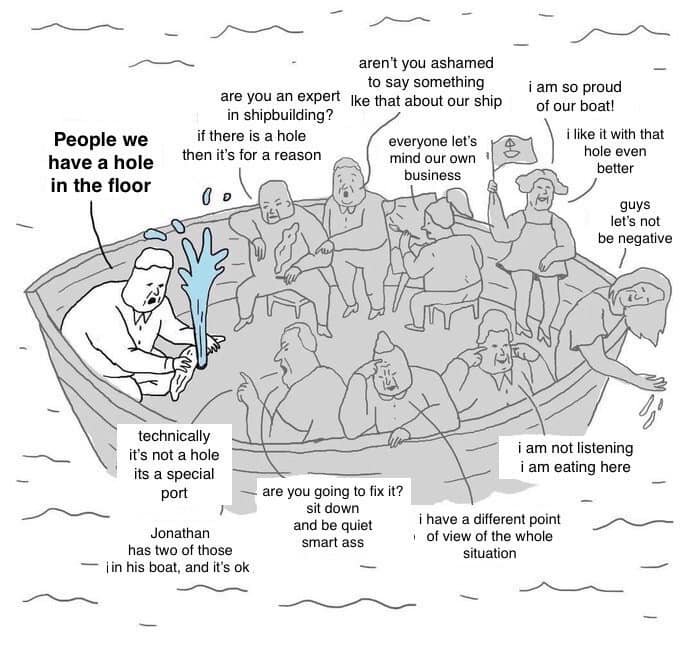

In tech funding, over the last decade, the #EU poured hundreds of millions of euros into the #blockchain mess. The promise has proven to be illusion, we built no working transformation: trustless systems, frictionless governance or new economic layers for Europe. The reality? By any honest social metric, 99.9% of that public funding was poured straight down the drain.

Now we are lining up to do the same with AI. Another wave of hundreds of millions, based on another cycle of hype, feeding frenzy for consultants, startups, and policy conferences. And if we are realistic, 99% of this funding will follow the same path: absorbed into closed, corporate-driven ecosystems with minimal public return, poured down the drain.

In between these two hype cycles, we invested comparatively little in the #openweb and #FOSS. And yet that is where we actually saw meaningful results. Even if we are conservative and say 70% of public funding for #openweb and Free and Open Source Software was wasted, that still leaves 30% that worked. Thirty percent that built tools people use. Thirty percent that created infrastructure that continues to function. Thirty percent that delivered measurable social good.

Compared to less than 0.001% meaningful return from blockchain projects (and that’s being generous), and perhaps 1% from AI funding (also generous), this is an extraordinary success rate. So why aren’t we talking more about this?

The Pattern: Funding the Closed, Ignoring the Commons

The problem is not technology, it’s political economy. Public money is repeatedly funnelled into closed ecosystems. #Blockchain projects were built around proprietary platforms, based on financialisation. They all failed to deliver public infrastructure, most were simply vehicles for extraction.

#AI is following the same pattern. Instead of building public infrastructure rooted in openness, transparency, and shared governance, we are too often simply subsidising closed models and corporate consolidation. The result will be the same: dependency, vendor lock-in, and very little democratic control.

Meanwhile, the #4opens and #FOSS quietly power the world.

- Servers run on open-source operating systems.

- The web runs on open protocols.

- Community platforms run on federated code.

- Critical infrastructure depends on open libraries.

And yet funding for these projects remains very marginal, precarious, and treated, if at all, as an afterthought.

Why This Matters

This is not only about waste, it is about direction. We are living in an era of climate breakdown, democratic fragility, and accelerating inequality. Public investment needs to strengthen commons-based infrastructure, not deepen dependency on mess of speculative and corporate-controlled #dotcons. When we fund the #fashionista hype cycles we increase centralisation, reduce public oversight and lock ourselves into closed ecosystems, which hollow out our needed local capacity.

When we fund #openweb and #FOSS we build shared infrastructure, increase resilience, enable local innovation to create tools that can be forked, adapted, and reused. Even a poor 30% success rate in commons-based funding creates compounding social value. Code written once can be reused globally. Infrastructure built openly becomes a foundation others can extend. Knowledge stays in the public sphere.

Closed projects don’t compound in the same way. They expire, pivot, get acquired, and then disappear behind paywalls.

The Incentive Problem

So why does this mess keep happening? Because hype is easier to support than maintenance. The current #mainstreaming is to blind, Blockchain and AI come with glossy narratives of disruption and geopolitical competition. They promise growth, dominance, strategic autonomy. They flatter policymakers with the illusion of being at the frontier.

The #openweb and #FOSS, by contrast, are mundane. They are about maintenance, collaboration, and long-term stewardship. They don’t produce any unicorn valuations, the smoke and mirrors that feed splashy policy headlines. But they work, and in public policy, “working” should be the gold standard.

What We Need to Talk About

We need to keep asking direct #spiky questions about what percentage of publicly funded tech projects remain usable five years later? How many are open, forkable, and independently maintainable? Who owns the infrastructure we are building with public money? And does this investment strengthen the commons or subsidise enclosure? If we measured blockchain funding by long-term public utility, it would be exposed as a massive misallocation at best and fraud at worst. If we measure AI funding the same way in five years, we may reach the same conclusion. We #KISS need structural change:

- Default to #4opens – Public funding #KISS should require open licenses, open standards, and transparent governance.

- Fund Maintenance – Not just #fashionista projects, but long-term stewardship of critical open infrastructure.

- Measure Social Value – Not hype, not valuation, not patents, but actual public use and resilience.

- Grassroots tech as seedlings – to be open to real change and challenge in tech.

- Support Commons Governance – Fund communities, not more startups.

Why We Need to Act

If we do not challenge the current messy #techshit cycle, we keep pushing ourselves into a future defined by the #dotcons, closed platforms with extractive models. To say this is not anti-technology, it is pro-public infrastructure. The choice is simple, do we keep pouring public money into, closed ecosystems with near-zero public return or invest systematically in the messy, imperfect, but functioning #openweb commons.

The data – even by generous estimates – is clear. Thirty percent real return beats 0.001% every time. We need to stop funding hype, we need to fund what works, and we need to say this loudly, before the next billion euros disappears down the same drain.